Eleanor Louise West photographed by Amanda Summons

Photo courtesy of the artist

Damaris Athene: Can you start off by telling me a bit about yourself, please, Eleanor?

Eleanor Louise West: Yeah, so I'm Eleanor Louise West, I use she and they pronouns. I was born in Portsmouth, and I did my degree at Camberwell College of Arts and I finished that in 2019. Since then I've been trying to create art outside of the institution, which has its challenges, but also is really exciting and has different opportunities. Hopefully, I can continue to do that.

DA: Nice, and could you say a bit more about your practice?

ELW: I started at Camberwell on the BA fine art photography course. At Camberwell all the fine art courses have labels, but it's really interdisciplinary. In the first unit the main question they set was, How do you not take photograph? That set me up for falling out of love with photography. I chose the photography course because I was like, well, I can't paint or draw, so I might as well take photos. But through my time at Camberwell I fell out of love with photography, especially as a queer woman photography has its own challenges around spectatorship and ownership of images. Through some external stuff I was doing with a queer craft club, I found I loved embroidery, and I found that a much better vessel to capture my ideas, especially around representation and how I wanted people to interact with my work. So since then, I've been doing lots of textile work. I really enjoy quilting, embroidery, anything that's soft and beautiful is kind of my thing! I've also been playing around with doing some illustration work, and I still do photography from time to time, but it's become part of my practice that informs my other work rather than being the work itself. That's not to say that I don't think photography can be an amazing vessel for queer representation. My main inspirations are still photographers, Tee Corrine and Zanele Muholi. But for me when I was taking photos of myself, and then presenting them (especially to an all male tutored course at university at the time) it didn't feel right for me. Everything is a lot about how my image, or images of people that I love, can be abstracted and used against them, especially as most of my subjects are queer and/or trans. In my second year, there was an associate lecturer who I had for all credits who was homophobic.

Safety First, 2019, Two Quilts with hand embroidery and digital print and bedframe

Dimensions variable

Photo courtesy of the artist

DA: How horrible. I can completely understand what you’re saying, especially showing work to an audience that’s mainly cis males. Your subjects can maybe be fetishised or viewed in a way that you really don't want them to be, and there’s that duty of care you have over the people that you're representing.

ELW: I was also told to think about my audience and who I was making art for. I learned quite early on that I was making work for a queer community. So then presenting that to mostly cis hetrosexual audience that was really male dominated was really difficult. For a crit, I chose to show a piece of work that I'd already shown to my community, that had really resonated with them, and they said “This doesn't teach me anything about your experience, I'm not getting anything from your work.” And I was like, well, it's not for you. I'm not your teacher. I'm doing this because I'm trying to find something that will resonate with my community, and teach them something. There was a lot of back and forth.

DA: That sounds so frustrating, you’re not there to educate them about the queer community.

ELW: There were a lot of good things about the course. But in the end, the tutors ended up being like, Do you just want to tell me about your work and I'll be quiet?

DA: So did you stay on photography, even though you were going into textiles?

ELW: I did. It never really occurred to me at the time that I should switch course, because I have a lot of internalised thoughts about talent. I thought, Well, I'm not a taught sculptor, I don't have any experience in sculpting, so why would I do that? It took me a while to actually recognise that the work that I was making was sculpture. At the time, there were quite a lot of people on photography making sculpture, but I was the only person working in textiles. I was pretty much solely self taught in that sense.

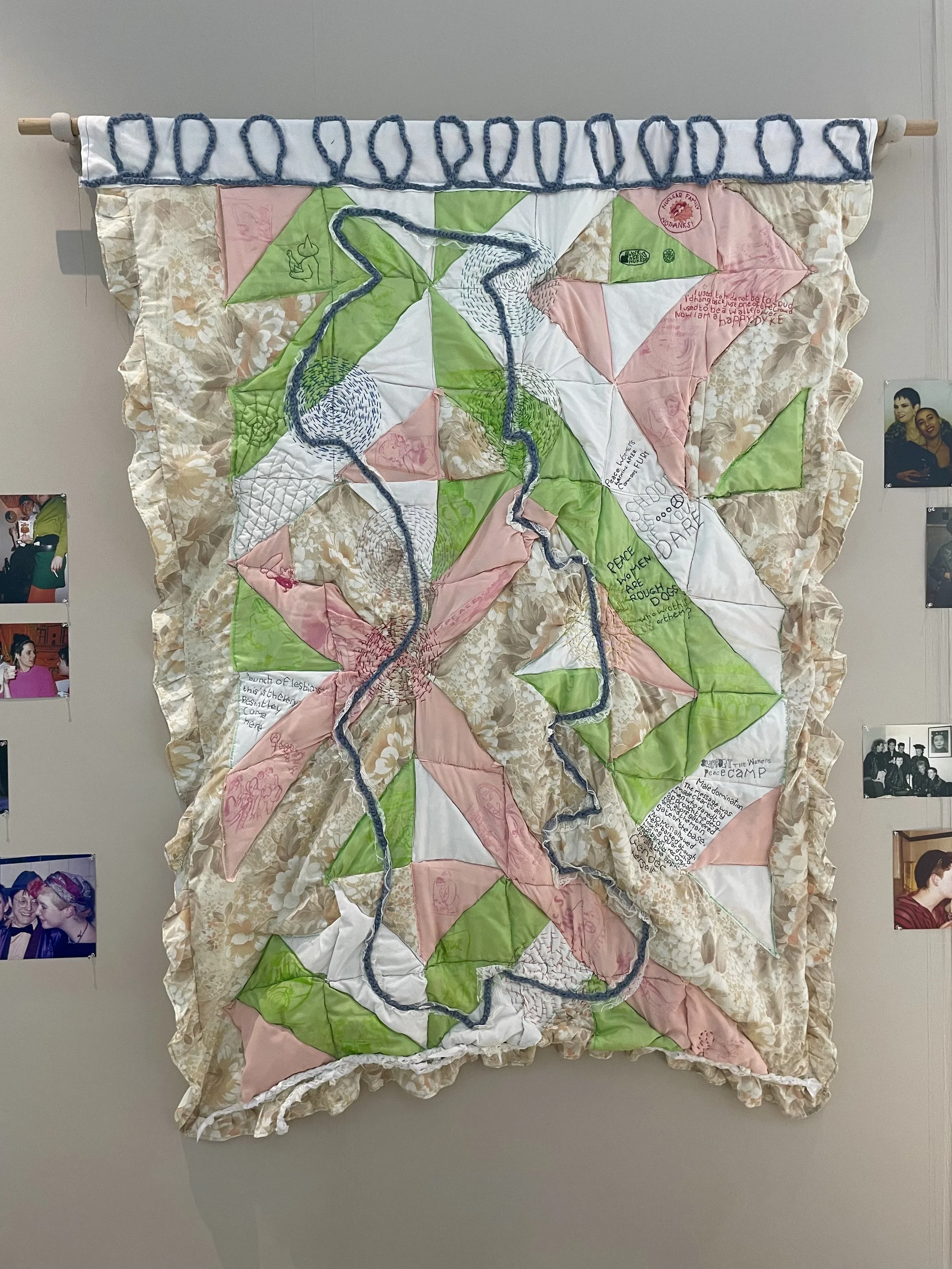

Work in Progress shot of Greenham Common, 2021, Textile quilt with thermal image transfer, hand embroidery, lace and crochet, 135cm x 200cm

Photo courtesy of the artist

DA: That must have been really hard, not really having anyone to guide you, or to have any peers that were doing similar things.

ELW: True. I think my practice was quite removed from the course, but a lot of the critical theory and the understanding, like ways of looking and the truth in images was really interesting to me.

DA: It's such a journey to figure out your niche! What draws you to working with textiles and crafts?

ELW: Textiles and quilts have a very long history in both feminist and queer culture, especially in activism. If you think about protest banners, or making a blanket for like a new baby or someone who's ill. I got really invested in researching Greenham Common, and the textiles that came out of that, like edited clothing, jumpers, banners even some of the tarpaulin structures that they made are really, really interesting. I think a lot about how textiles are considered a lesser art, that they’re a craft rather than an art, and they're particularly feminine. As someone who's gender queer, it’s really interesting to play with that, especially when I use quite “masculine” imagery. It's a play between this really feminine, pink, girly free thing and also my own identity.

DA: That's fascinating. Textiles have a real power to be subversive because of the weight of that history and all of the connotations wrapped up within it. Could you speak a bit more about how you explore your experience as a queer person in your work?

ELW: So the first queer piece of art that I made was a screen print of a campaign by Act Up, an American gay rights movement thing. They protested the film Basic Instinct, because they disagreed with the way a bisexual woman was portrayed. They had this really iconic phrase, which was, ‘the lesbians always end up dead, and the bisexuals always end up with the men.’ I made some screen prints replicating the poster they made. I found it really interesting. Moving forward, I've been thinking about communities of care, especially as a queer femme being sort of a mother to a lot of younger queer people. I spent a lot of my time online in my early youth interacting with people who were maybe like a year or two younger than me in their journey of coming out. For a lot of people looking at me and my partner was really affirming, because they could see that queer people have a future. Queer elders nourish a community of queer people, and bring them together, even when their families reject them. I will always try and explore things that I've personally experienced and translate them to try and capture those feelings and see if they resonate with other queer people. I try to do that in an affirming way to be like, look like, this is us, but we get through it.

Catherine Did It! , 2017, Screen Print, A4

Photo courtesy of the artist

DA: How does that manifest aesthetically in the way that you make things?

ELW: I'm really captured by John Walters’ idea of shonky art, which is kind of the uncanny, but in many ways, a little bit shit. But that's what makes it brilliant. Quilting takes a lot of maths and sometimes you don't get it right, but embracing that and having repairs in it, that in itself is queer. It's making good, you’ve been dealt the cards you have been so I try to bring it together to make something which is bright, colourful, soft, and cute. That's really engaging for me. I try and embrace the mistakes I make. There's a difference between a work being technically perfect and a work being right.

DA: Totally. How does Cold War Civil Defence imagery come into your work?

ELW: From a young age I've been really interested in dystopian, apocalyptic novels and I think, in many ways, the reason why I'm drawn to them is the idea of society starting anew. Not that I'm for nuclear war! But I think there's something interesting in looking at the way the authors portray society rebuilding or the way that communities are formed after that. In my second year I read ‘Octavia's Brood’ which is a collection of speculative science fiction for social justice. There are a lot of women authors, a lot of women of colour, actually, and queer women in that book. Something really resonated with me. I also have really big interest in history and the Cold War is such an interesting time, because we have Margaret Thatcher's Reign of Terror, the AIDS crisis, which is obviously horrific, and then alongside that we have the bubbling tension and anxiousness of a nuclear threat. All that compounded, I find it really interesting. I started looking at Civil Defence guidance that the government brought out in the 80s, especially 'Protect and Survive'. It's a series of videos and a booklet, which attempt to guide the public to survive a nuclear war, and everything is so silly and morbid at the same time. It's like, put some doors up against the wall - and that's gonna save you from a nuclear weapon! Obviously, that's nonsense. But I was trying to think about how, as a queer person, I'm disabled and I'm queer, but I'm still white, and I'm still relatively cis passing. When I talk to other queer people, sometimes it can feel like, even using my experience, or even just talking to them isn't enough, because as one person I can't make a change. I can't fund people to leave their homes as one person. I can't lobby the government on my own. I was trying to think about the things I can do like creating community, creating comfort, talking to people. A lot of my work has sort of honed in on the shelter aspect of the defence guidance, but how we can make physical or theoretical shelters for our community, safe spaces. It is really beautiful graphically as well, and a lot of it focuses on home. As a queer disabled person my life and community is very different to someone who's able bodied because I can't get into many clubs, especially in London. My queer and gay scene is very different to some other people's queer and gay scene, because I physically cannot get into spaces they inhabit. So thinking about how I bring the community into my home or in spaces that I can access and using that as a queer space. A queer heterotopia if you will. *laughs*

Greenham Common, 2021, Textile quilt with thermal image transfer, hand embroidery, lace and crochet, 135cm x 200cm

Photo courtesy of the artist

DA: *laughs* I like it. Eleanor for Prime Minister! That's so interesting as well as the all the Cold War imagery is all about the military and traditionally masculine, and then you’ve combined it with these traditionally feminine quilts and craft making a really interesting symbiosis between the two.

ELW: Yeah, when I was researching for my degree show piece I was using a clip from the H bomb, a film that was produced for civil defence workers to understand the horrific magnitude of what a hydrogen bomb is compared to an atom bomb, which is like 1000 fold the damage or something ridiculous. I went to the Imperial War Museum, dressed head to toe in pink looking my femme self, into an office full of men being like, Can I see this film? It was such a strange experience, because they were kind of suggesting other things to me. I was like, actually, I'm not really interested in how big the guns were. I'm interested in the effect that it had on people. I was there to see the nuclear exhibit, which touched very briefly on Greenham common. I think especially when people are interested in history a lot of it could be perceived as glorification of war, which makes it really inaccessible. A lot of my research comes from Julie McDowall. She's a Scottish nuclear war researcher who researches the civilian stuff.

DA: What a strange experience! What barriers have you faced to making art?

ELW: Space, money, time, the usual. I'm the first person in my family who has had the privilege of attending university, but also outside of that I'm the first person in my family with an interest in the arts. So trying to explain to my family that this is what I'm doing, isn't that cool? They were like, “I thought you're going to be a cruise ship photographer, why are you doing this?” Also, being working class, a woman and disabled in the arts is the worst. I also need to rebuild my confidence after my degree, I had quite a lot of traumatic experiences with tutors on the course. I'm really thankful I had a really strong queer community outside of university at the time because they kept driving me to make and they kept giving me actual feedback on my work. The real thing is accessibility. A lot of small galleries do not have lift access, or they're in a basement or they're up three flights of stairs. So actually finding places where I can exhibit work and install work is a challenge in itself as well.

Pressed, 2018, Digital Print with Traditional Letter Press, A4

Photo courtesy of the artist

DA: That must be so difficult. So many small galleries are really inaccessible.

ELW: It's such a shame. I understand why those places are where they are because they’re small arts organisations and they might not have the money to rent somewhere accessible. But as an entry level and early career artists, it's kind of the places where we have our opportunities. So it's a continuous cycle of not getting opportunities, because I can't access them but they’re the ones that are at my level and I’m not qualified for the bigger places yet.

DA: It's a struggle even if you're able bodied, so I can't imagine how difficult that must be if you can't actually access those spaces. How do you usually work? Did you find that's been affected over the last year?

ELW: Actually, it's been quite useful being able to work from home, because I was able to sit in meetings with my camera up while I sew, which definitely helped for a lot of my projects. Also cutting the commute time, which can take two hours out of your day, two hours that you could be making art. The only thing is that there has been a drop off, obviously, in physical exhibitions, and as a sculptor you want the world to be seen and or touched. But online opportunities have been on the up, which has been really exciting because I can actually access those opportunities, because there's no stairs required! It's been good and bad, but I've always created from home anyway, even when I was at university.

DA: It’s great that now we can see exhibitions online, even though has its limitations.

ELW: It's limited, but it means that people outside of London and people who don’t normally have time to go to galleries can see my work, which is exciting. I've been thinking more about how my work lives on social media, because social media is very accessible.

Bedroom Debris, 2021, Textile quilt with hand embroidery, shrink plastic, handmade paper and crochet, 20cm x 8cm

Photo courtesy of the artist

DA: I'm interested to see how that develops! What would you like people to get from your work?

ELW: I have thought a lot about where my role sits as an educator and as an artist. I think it's really important for queer people to understand that they don't have to make work that straight people get. Your role doesn't have to be that of an educator. If that's work that you want to make, and you have the mental capacity, stamina, and quite frankly the thick skin to be able to do that, that’s really amazing. But if you are interested in making work that maybe can only be understood by a specific community, being empowered to still create the work is really important. In my work I describe the anxiety that can be felt as a queer person, so I hope that people could look at that work and see themselves in it, and gain comfort in that. When I was coming out, having a community around me that understood what I was going through and the challenges that I was facing was sometimes enough, even if there weren't answers.

DA: Have you had any reactions to your work that really stick in your mind?

ELW: As a textile artist, one of the most frustrating things is when people touch your work. Also I made a quilt, that unfortunately has since been destroyed due to studio clear out and a mix up, which had lots of small patches with the 'Protect and Survive' logo with things inside it. One of the patches said ‘Set boundaries’ and one of the people in my chosen family really resonated with that part of the work and actually now has it tattooed on them!

DA: Wow!

ELW: That's a reaction I'd never expected, that someone would want my textile work on their body forever, potentially. I don't know whether I want to remake that work because it's a work that I really liked, but I also think it's really exciting and kind of poignant that the only iteration of the work that exists outside of photography is on somebody's body.

She/They Collar, 2021, digital work including a handmade collar hand embroidered and a self-portrait of the artist (made as part of 30 days 30 works by the 12ocollective)

Photo courtesy of the artist

DA: How interesting! Whose work inspires you?

ELW: Allyson Mitchell, a lesbian textile artist, with the iconic Hungry Purse piece. It's this massive yonic structure which is built out of reclaimed textiles. There’s a lot of crochet and stuff they found with charity shops. One of the first queer artists I really resonated with was Tee Corinne, a lesbian photographer. She used solarisation to abstract her subjects, to still represent them while protecting the subjects’ identity. It's really interesting the way it plays into the resistance of sexualisation of those bodies. One of her most famous works is the Yantras of Womanlove series. It depicts all types of lesbians, lesbians with mobility aids, fat lesbians, it's really cool. A more contemporary photographer I'm really inspired by is Zenele Muholi. They are a South African artist who takes pictures of their community. I'm interested in their 'Somnyama Ngonyama, Hail the Dark Lioness' series, where they use household materials to abstract themselves while making themselves into women figures of their history. I love textiles, but I'm also very heavily interested in photography. Also, Daniel Fountain is a living artist who’s very good. He makes quilts and they are amazing because it there's a lot of repair and rebuilding in them.

DA: I’ll have to look up the people I don’t know! What projects have you been working on recently?

ELW: I had an exhibition in Kennington at the end of September, and there's hopefully some exciting stuff coming out that exhibition, thinking about the longevity of that work. I made a quilt based on Greenham common. I don't have any more exhibitions planned in the near future, but I do have a lot more collaborative work plans. I'm currently helping my partner with their installation for the Greenwich Docklands festival and I’ve got some other collaborative projects coming up with them.

Quarantine Quilt, 2020, Textile Quilt with hand embroidery, 25cm x 25cm

Photo courtesy of the artist

DA: Have you got any other plans for future work?

ELW: Yes, I've got a lot of different works planned. With my partner we're making a quilt, which is based on the bank of community, I don't know if you've heard the phrase 'We're all passing around the same time 10 pound note’? We're physically making a massive quilt that’s the 10 pound note. With fundraisers for queer disabled people, queer people, and trans people, it does feel like it's always the same money doing the rounds, which is really useful because it means that when people need the money, they can get it. It also means that there's a feeling that if you were ever in trouble, there would be people around you to help. Other than that, I want to start making work in response to a lot of the science fiction that I've been reading recently. I've been reading a lot of Octavia Butler, and the way that they create worlds and futures is really interesting to me.

DA: I look forward to seeing what you make. Thanks so much Eleanor!

ELW: Thank you!